The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), established under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022, prompted a wave of interest in green banks nationwide—including here in Washington. This is because the GGRF was designed to provide grants to eligible entities, including green banks that would in turn provide loans, grants, and other forms of financial and technical assistance to clean energy projects. The Clean Energy Transition Institute (CETI) described the GGRF’s origins and design two years ago with the blog Understanding the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.

Clean energy financing is a critical component for accelerating the clean energy transition, and green banks can play a major role in advancing equitable climate finance. While the fate of the $27 billion that the U.S. Congress authorized for the GGRF is anything but certain, the Washington State Green Bank (WAGB) was established on November 4, 2024 with the creation of its Board of Directors and funds allocated through the state’s Climate Commitment Act (CCA).

This Deep Dive explores key characteristics of green banks, explains the role they can play in clean energy financing, and introduces the recently established WAGB.

A green bank is a financial institution that aims to make clean energy projects more affordable by offering innovative financing and tools to fill gaps in the market, often financing projects that otherwise would not get funded. While many banks around the world have committed to reducing emissions, green banks intentionally focus on sustainability and are willing to assume higher risks and lower profits. Green banks can range in design from:

Most green bank entities are limited to specific geographic boundaries due to their source of funding, but some, such as Inclusive Prosperity Capital, are national nonprofits that can finance projects in any location.

Some green banks also have a specific focus, such as serving low- and moderate-income neighborhoods or financing projects related to buildings, while others are broader in scope. Green banks also sometimes administer city or state programs, such as the Connecticut Green Bank with Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE). C-PACE is a financing structure that allows building owners to borrow money for energy efficiency, renewable energy, or other projects and make repayments in the form of an assessment on the building owner’s property tax bill.

Green banks can help finance a variety of projects, including solar panels, energy storage, zero-emission vehicles, energy efficiency retrofits, geothermal heat pumps, and electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

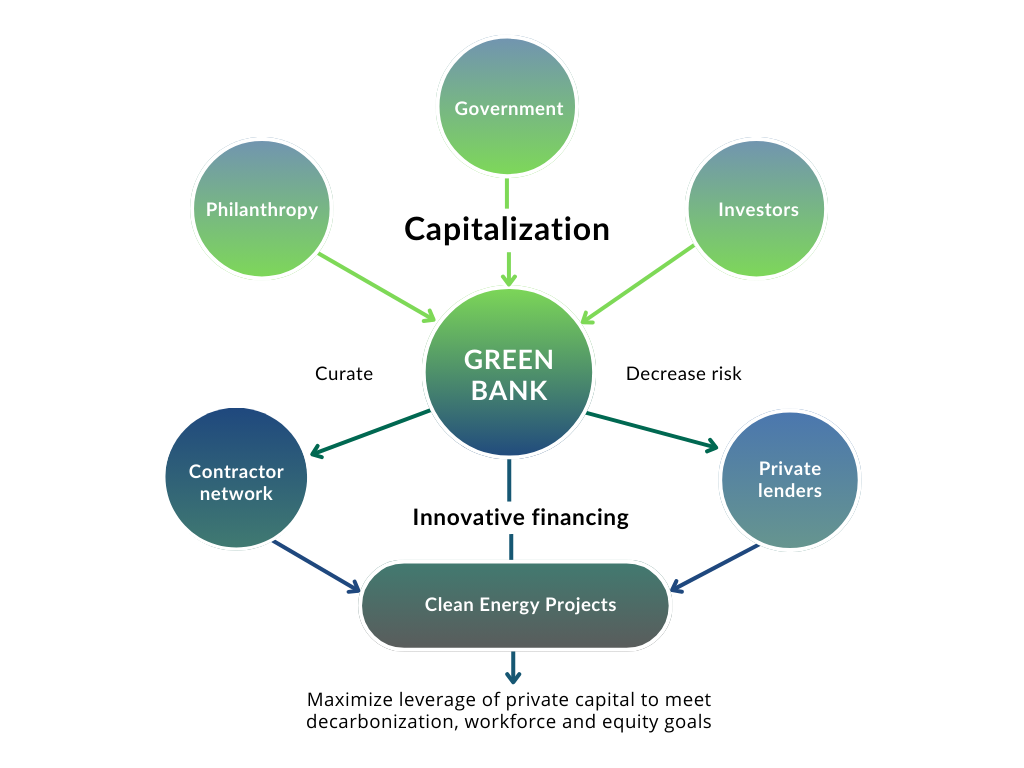

Figure 1 below shows sources of capitalization (i.e., funding sources, explained in more detail in a later section of this blog), as well as how funding can flow through innovative financing mechanisms to fund clean energy projects. A green bank might partner with private lenders, work with a network of contractors, and/or provide financing directly for clean energy projects.

Regardless of the exact structure, all green banks generally share these characteristics:

Green banks can be funded through a variety of sources, including philanthropy, private capital, government funds, public revenue, or some combination of sources. By design, green banks aim to leverage public revenues to mobilize private capital investment.

To get a sense of the array of funding sources used, take the Connecticut Green Bank as an example. According to the organization’s Comprehensive Plan: Fiscal Years 2023 through 2026 (see pages 46-49), the Connecticut Green Bank pursues the following funding sources:

The $27 billion GGRF, administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), was designed to provide grants to eligible entities, including green banks that in turn would provide loans, grants, and other forms of financial and technical assistance to projects.

The GGRF included three programs: a National Clean Investment Fund (NCIF, $14B) that would fund national nonprofits to make direct investments providing financial products and supporting qualified projects; the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator (CCIA, $6B) that would pass funding through to community lenders; and Solar for All ($7B) that focused on expanding low-income and disadvantaged community access to residential and community solar, along with storage and enabling upgrades.

At the time of writing this blog, the EPA has terminated all three GGRF programs, creating significant uncertainty and distress for grant recipients and the communities they serve. The recipients are challenging these terminations in court, but lawsuits could take years to resolve.

In February 2025, NCIF and CCIA grant recipients whose grants were held at Citibank lost access to their accounts, setting off a series of lawsuits from the nonprofit recipients and Citibank. The $7 billion Solar for All funding appeared safe until early August 2025, when the EPA announced that it would terminate that program, too, of which only $53 million had been spent to date nationwide.

The WAGB is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit financial institution established in fall 2024 with help from the Washington State Department of Commerce, the City of Seattle, and $800,000 in initial capital from state’s CCA. The WAGB is led by Executive Director Eli Lieberman and a Board of Directors that includes CETI’s own Eileen V. Quigley.

The WAGB plans to provide accessible financing for energy efficiency and renewable energy projects, focusing on three key areas:

The WAGB held its inaugural Stakeholder Workgroup on July 31, 2025 (slides and recording from the event are available). The event brought together key partners to explore how green banks can close funding gaps and accelerate the clean energy transition. Presentations included Lieberman’s introduction to the WAGB, insights from the well-established Connecticut Green Bank, and innovative financing models and needs across rural, agricultural, and Tribal communities. Finally, there were breakout sessions where attendees discussed climate finance gaps in Washington and where the WAGB should or could begin its work.

Lieberman’s presentation identified several key barriers that the WAGB will attempt to address: a fragmented financing landscape; lack of low-cost, flexible capital; customer and contractor uncertainty; an insufficient contractor network; the split incentive problem in which landlords are not incentivized to invest in energy improvements; limited solutions for small commercial buildings; and equity access issues faced by underserved communities.

With the GGRF funds currently frozen in bank accounts and not available, the WAGB will need to pursue alternative funding resources beyond the original $800,000 from the CCA.

Green banks have the potential to play a transformative role in advancing an equitable clean energy transition in the Northwest. While recent federal actions have introduced considerable uncertainty and disrupted momentum, the WAGB presents a valuable opportunity to bridge financial gaps and help the state continue to make progress toward achieving its clean energy goals.

To stay informed about WAGB activities, you can sign up for updates on the WAGB website.

If you want to receive updates from CETI straight to your inbox, subscribe here.